Le Four Seasons Magazine est le magazine exclusif réservé aux clients des hôtels et centres de villégiature Four Seasons.

Le Four Seasons met Tunis à l’honneur dans tous ses hôtels dans le monde

Selon son éditeur le Four Seasons Magazine cible environ 1.1 millions de lecteurs.

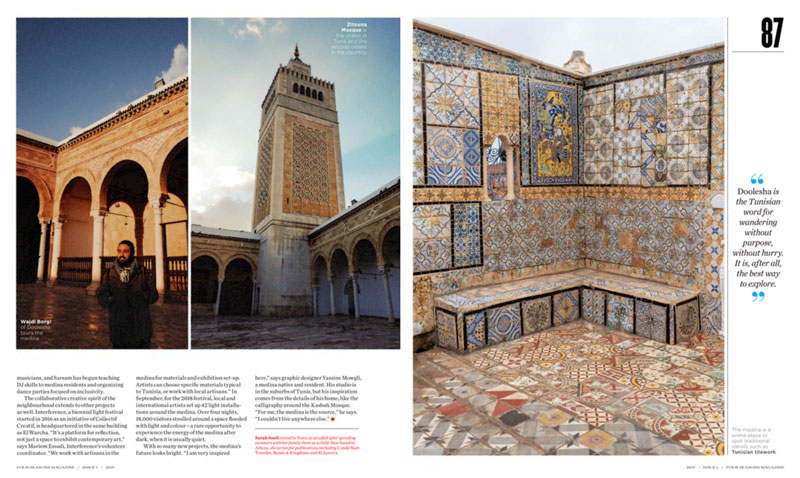

Extrait du texte écrit par Sarah Soull Photos de Grant Legan

In the centre of Tunis, THE OLD MEDINA IS HOME TO TRADITION: The same families live in the same buildings; calls to prayer pierce the air at the same times every day; stone streets are worn from generations of footsteps. Yet, with most of Tunisia’s population under the age of 30, it’s in the medina that YOUTH AND CREATIVITY are making their deepest marks. Taking time to wander through it is the best way to see the city’s personality unfold.

"IN THE MEDINA, if you speak Italian, French, Hebrew, Greek or Maltese—well, the walls would smile, because they have all of these memories," says Wajdi Borgi. He’s one of the founding members of Doolesha, an innovative tour group that offers a creative way to explore the medina of Tunis. A group of university students were leading architectural tours; their walking conversations evolved to include different points of view and opinions; and then the tours morphed into urban experiences geared towards artists, musicians and other "culture producers." Doolesha now offers micro and macro views of the medina, with tours based on food, anthropology, ethnicity, architecture, art and history.

Borgi and I are sitting in a rooftop café in the heart of one of the best-preserved medinas in the Arab world. Around us are TV antennas, laundry drying in the sun and stray cats nimbly jumping across the roofs. It’s the feline version of doolesha—the Tunisian word for wandering without purpose, without a fixed agenda, without hurry. It is, after all, the best way to explore. "In the medina, it’s like time is suspended," Borgi says, "and that gives us the possibility of artistic expression."

A SPACE OUTSIDE TIME

Many twisted paths feed into the ancient medina. Its principal mouth is the beautiful Bab el Bhar (literally, "Sea Gate"). The main avenue of modern Tunis that leads to this archway is full of cars, mannequin-stuffed storefronts, and the hectic sounds and movement found in any metropolis. A large clock tower looms over everything, a constant reminder to hurry.

But pass through Bab el Bhar and you forget about the clock. Here in the medina—the heart of Tunis, named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979—time seems to expand, and you find yourself wandering through the centuries.

Founded in AD 698 with the Zitouna Mosque, the medina grew in earnest in the 12th and 13th centuries, during the rule of the Hafsid dynasty. New people, cultures and languages arrived via the Mediterranean Sea: Andalusian Muslims, Turkish Anatolians, enslaved West Africans, and, later, waves of Italians, Greeks, Maltese and French. Historically, a mix of Muslims, Christians and Jews has always populated the area.

"This is what the medina’s identity has always been—really cosmopolitan," says Youssef Ben Ismail, a Tunis native now at Harvard University in the U.S., working on a doctoral dissertation on the history of Tunis during the Ottoman Empire. In the 1950s and 1960s, after Tunisia gained its independence from France, the character of the medina began to change as many non-Muslim Tunisians moved away. Aside from the stalwart souks, still organized by trade (perfume, gold, spices, leather), the medina remained largely residential.

In the past few years, though, there’s been a resurgence of the old cosmopolitan energy as young native Tunisians and immigrants have breathed new life into the space. Recently, Doolesha has expanded to include another project, Doora-Fel-Houma, which teaches residents 18 to 30 years old to reclaim their living space by leading their own neighbourhood tours.

Emily Sarsam, originally from Austria, moved to Tunis permanently in 2018 after five years of living there intermittently. She has been involved in several of these revitalization projects, including the launch of Journal de la Médina, a newspaper created for and by the people of the medina, and also ran the medina’s first co-working space, Dar El-Harka. "The medina o—ers a sense of community in a city that can otherwise be anonymous," Sarsam says. "You can connect with people more easily here."

CREATING SOMETHING NEW

Wherever you look, the medina’s history is inescapable: Delicious fruit tarts are a reminder of the French culinary influence; wrought-iron balconies recall generations of Italian residents; stone walkways are worn smooth by centuries of pedestrians.

But one distinctly new sight is collaborative design studio El Warcha ("The Studio"), launched in 2016 by Benjamin Perrot, a French designer and educator living in the medina and in London. By providing space and materials for neighbourhood residents to create things like furniture and art installations, El Warcha promotes alternative forms of education and civic action—in essence, a democratization of design. At the moment, El Warcha is based in an old house full of history, complete with an inner courtyard, tiled walls and plastered ceilings. "Being in the medina means we are part of a supportive community," Perrot says. "The people we work with are our neighbours—young people and creative people."